The More Tooth the Better!

There are a lot of things that we perform differently in true clinical practice as compared to what we learned in school.

All dentists can attest to that. From simple things like differences in materials to technological changes such as Cone Beam Computer Tomography (CBCT). And certainly there are very good reasons for the schools that we attended to keep some more advanced concepts, types of materials, philosophy of practice and so on and so forth from us. There is so much information about dentistry that 3-4 years of dental school could never allow and advanced training that would need no further learning. As our careers in a ‘dental practice’ suggests, we are always practicing; always learning, progressing, changing, and improving.

But what I find when I attend continuing education courses, conferences, and the like is that there is a focus on the major developments. For example at the AAE (American Association for Endodontics) there is a heavy load of information about CBCT imaging, or new and improved rotary instrumentation, or a strong focus on the microbiological processes we are trying to heal. But what is left out too often is just the simple things.

So for this blog I want to focus on one very simple concept that for me has changed so significantly in the last 10 years of private practice. I want to focus on the conservative accessing of teeth in endodontic treatment. I doubt any dentist could find a continuing education course on this subject by itself.

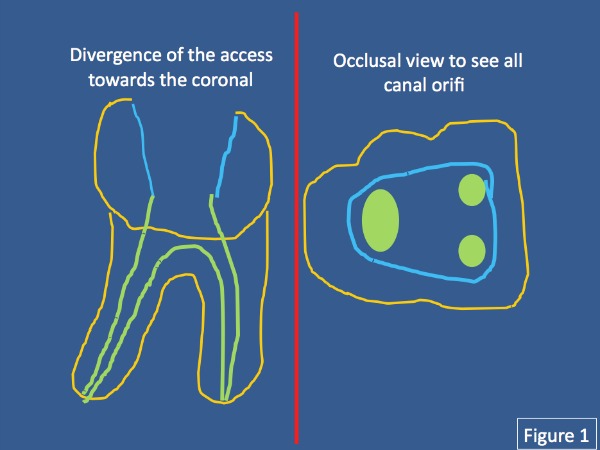

As I was taught both in dental school and in endodontic residency is that the access of the tooth occlusally should follow three principles:

- The access cavity should be divergent towards the occlusal cavosurface (figure 1)

- The access cavity should be large enough so that when viewing through the mouth mirror held in one location the operator should be able to see all canal orifi. (figure 1)

- It is important to obtain straight line access to all canals.

Even the most popular endodontic text books have spoken to this preparation form. The thought is that it allows for better treatment as a result of improving visibility and lessening stress on our rotary files. Certainly this seems reasonable; the more you can see, the better results you should get. Additionally from a dental school teaching perspective it also makes a lot of sense so that all students can be taught at a level and attainable expectation for this part of the root canal process.

However I have come to feel very differently. My access forms for root canal therapy are considerable smaller than when I was in dental school, residency, or even 5 years ago when I was into private practice. I actually feel that my access preparations are smaller this year as compared to last year. I think it would be accurate to say that my current access preparations conserve upwards of 35% more dentin than when I first started performing root canals. Another way to think about it is that we are saving 35% more tooth. Of course this will result in an overall stronger tooth. In the end a stronger tooth has a better long term prognosis. That reason alone is enough to support the concept of conservative access preparations.

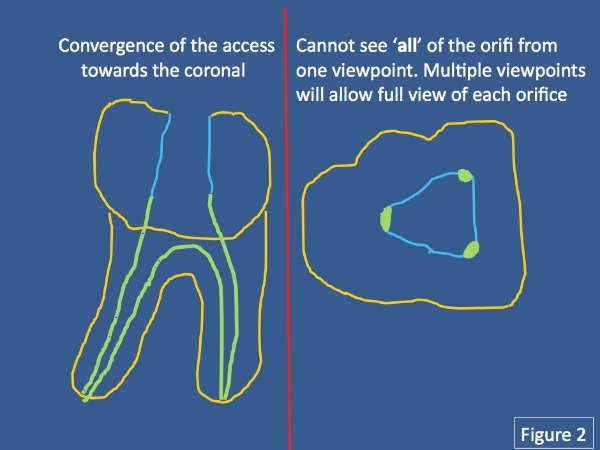

So let us now change those original two principles listed above.

- The access cavity in most cases will be convergent towards the occlusal cavosurface (figure 2)

- The access cavity should be large enough to allow proper viewing of all canals and possible atypical anatomy, but they do not have to be viewed simultaneously from one angle. Rather the canals should be seen with any change of viewpoints or angulations of the mouth mirror.

- Straight line access while nice is not always critical.

This 2nd principle is more subjective as it can be different for each operator and their comfort with what they see and how much they can see. The four of us in our office all have very similar feelings and comforts for this second principle; however there could be many other dentists or endodontists that require more space or maybe even less for what they would consider comfortable viewing of the canals. The key though is to find the balance between conservatism and saving tooth structure, yet not compromising the quality of the treatment. The ability to see what is being done is of course extremely important. And if one must error one way or another then visibility will trump saving more tooth structure.

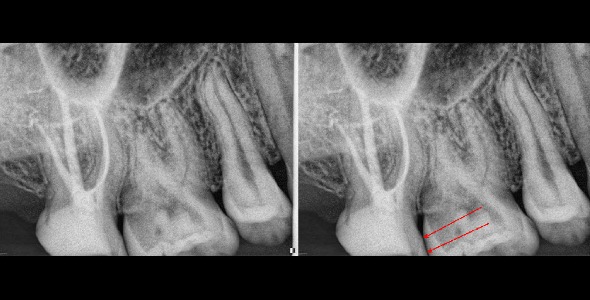

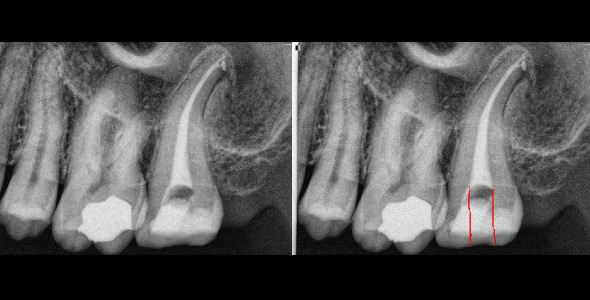

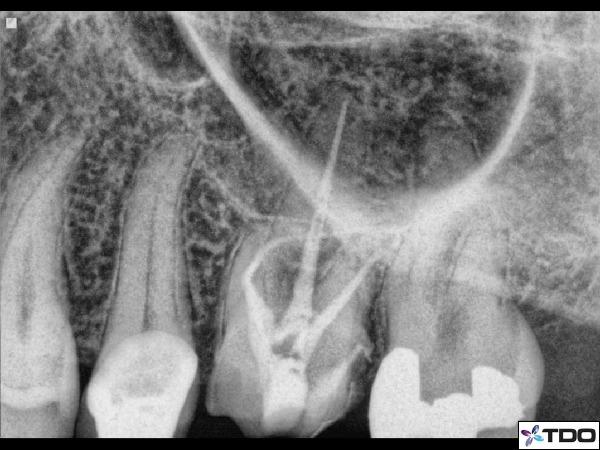

We all have been in countless situations where removing extra tooth structure is just an absolute necessity; you cannot treat what you cannot see. For example, maxillary second molars that are buccal and/or distally angulated. In these situations we will need to encroach upon the mesial marginal ridge, or the MB cusp, or the MP cusp in order to see (figure 3 and 4).

Figure 3: Here is a maxillary tooth #2 that I had to encroach upon the mesial marginal ridge more than I would have liked (red arrows). However there was such a limited mouth opening that the only way to reach and see the MB and MB2 canal was to remove more tooth upon the ridge.

Figure 4: Here is another 2nd molar tooth #15 in which I had to remove more mesial root structure than I would have liked. However the tooth was so long that in order to get access to the apex I needed to use a longer rotary file set which meant that I needed to tild the access towards the mesial so that the longer file would fit. On the right side I have drawn in red where I feel the ideal spot for access would be placed which is more centered.

Another example would be in retreatment scenarios that have a post to remove. We would need to open larger coronally in order to gain access to the lateral sides of the post/cements/dentin to dislodge it (figure 5).

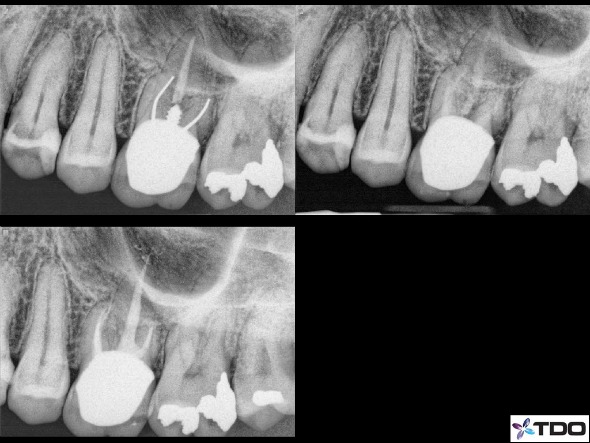

Figure 5: Here is a case in which the MB and DB canals had a silver point and the P canal had a wide post. I therefore needed to open the access larger in order to use the various instruments to retrieve the silver points and the post. Even though you cannot see the access size with the crown in place, this is a good example of a retreatment case that will require a larger coronal access.

The radiograph in the upper right is with all materials removed and calcium hydroxide in place. The lower left if the immediate post-op x-ray.

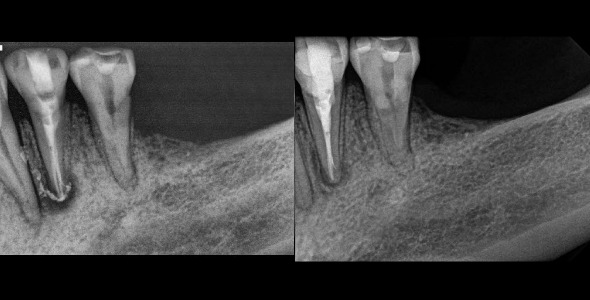

A third reasonable common situation would be atypical anatomy of premolars such as multiple canals (figure 6).

Figure 6: Premolar tooth #21 with 3 canals. I had to access larger than usual in order to find the canals. A smaller access could have resulted in a missed canal that would lead to endodontic failure. The radiograph on the right is the 6 month recall showing excellent healing.

Typically a premolar access form would be very small, but when multiple canals are identified radiographically/clinically/CBCT imaging then opening the access cavity larger to gain access to those extra canals makes a lot of sense. These are a few common experiences we will have, but there are certainly many other scenarios that are specific for any given case and would justify larger access forms.

Returning back to what we feel is the singular reason for conservation of tooth with the access is that it results in a stronger tooth. Let’s consider a few of the places where a tooth derives a lot of strength. The marginal ridges of molars, premolars and anterior teeth serve as a bulk of support for those teeth. Interference of those areas will of course weaken a tooth. A class 3 MOD filling on a molar will certainly weaken a tooth more than a class 1 occlusal filling. Thus if we can try to keep our endodontic access cavities more centralized and keep marginal ridges with a bulk of tooth structure then we can keep the tooth stronger. This is slightly different than what is taught in schools in which the mesial marginal ridge is not kept as sacred. Another important area to try to avoid is accessing too close to the cuspal tips of molars, incisal edges of anteriors, or too far linqually/palatally on the incisor cingulum. Again a more centralized access form will result in a stronger tooth remaining. Additionally, when working upon porcelain crowns there is less fracture potential with more bulk of porcelain. Thus less infringement upon the lateral surfaces of the porcelain will allow more bulk of material. (See figures 7, 8)

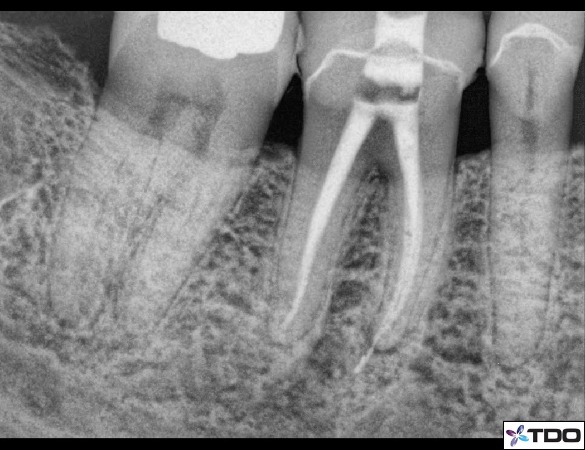

Figure 7: A conservative access form with a convergence towards the occlusal and preservation of mesial tooth structure.

Figure 8: Another access form with convergence towards the occlusal. This access cavity is quite centralized in the molar in both the mesial to distal direction and buccal to lingual direction.

So then this begs the question of how can we obtain straight line access into the canals if we are also trying to avoid these areas and conserve dentin. Straight line access is preached so strongly in most any endodontic course taken and even in continuing education around the world. The answer is that we do not necessarily require straight line access. We can make use of our materials and instruments to access into canals at angles. Specifically nickel-titanium , microscopes, pre-bent handfiles, endodontic explorers, smaller (size 1) mouth mirrors, ultrasonic instrumentation, etc. With a careful and mindful approach to each canal that does not have straight line access we can avoid the complications of file separation, canal transportation or blockage. (figure 9, 10)

Figure 9: A conservative access form very centralized in the tooth. I need to keep this access central so not as to interfere with any lateral walls which would impact the retentive value of the crown to be place. You can see I did not at all have straight line access into the MB or MB2 canals, but the curvature was still managed carefully.

Figure 10: Another very curved canal that I did not attain perfect straight line access on the MB or MB2 canal. The access is very centralized. The illustration on the right with the red shows the location of my access through the crown.

I have to be careful though with this point as taking a NON-straight line access approach does increase the potential of mishap (file separation, ledging, blocking, stripping). Thus each operators comfort level must be taken into consideration. What might be comfortable for me could be less comfortable for another or vice versa.

This blog is simply something that I have thought about over the past several years and something I felt was fun and worthy to write about; something to give a bit of insight into a regular and often overlooked part of endodontics. But also I want to point out it is just our approach to access preparation forms. I do not at all mean to say it is the only approach. There are many ways to practice dentistry and most all of them are right and appropriate. I would not want to discourage any dentist or endodontist from doing RCT’s the way they feel is most comfortable. And as always, your thoughts and ideas are valuable to me as well!

Thanks for visiting Tri City and Fallbrook MicroEndodontics!