Extra Canal Invasive Resorption – Part 2

This is the continuation of a blog I posted a few weeks ago.

Extra Canal Invasive Resorption (ECIR) is a type of external root resorption that usually starts in the cervical region, below the epithelial attachment of any permanent tooth, leading to the replacement of tooth structure with highly vascular tissue containing clastic cells. The rate of resorption can vary, however if left untreated, teeth with ECIR lesions are often lost. Please refer to part 1 of this blog HERE for a more in depth review of the classification of ECIR lesions, etiology, and clinical/radiographic/CBCT presentation.

Histology

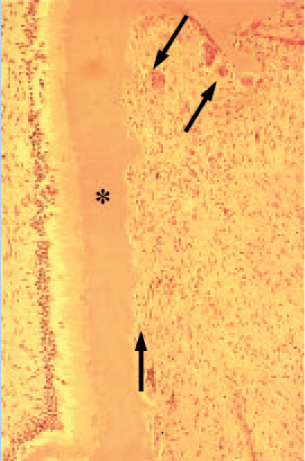

H & E staining reveals the resorption tissue as a highly vascular granulation tissue containing mononuclear and multinuclear clastic cells, and resorption lacunae (See Figure 11). Typically there are no acute or chronic inflammatory cells present, unless periodontal microorganisms secondarily infect the area. It is common to find an intact predentin/dentin layer protecting the pulp, however this layer may be breached in very large Class IV lesions, resulting in pulpal perforation.

Figure 11- Arrows point to mononuclear and multinuclear clastic cells and resorption lacunae. The asterisk labels an intact layer of predentin/dentin protecting the pulp.

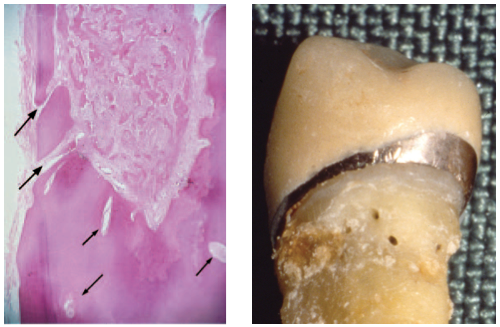

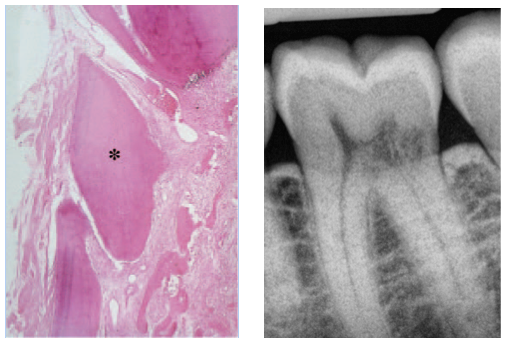

Since ECIR lesions originate in the periodontium, there will always be a communication with the PDL, which can be large and cavernous or pinpoint (See Figure 12, 13). Islands of bone-like hard tissue may form in large lesions, which accounts for the trabecular type pattern sometimes noted radiographically (See Figures 14, 15)

Figures 12 and 13- Arrows point to multiple pinpoint channels communicating with the PDL and extending into the radicular dentin. Clinical photo of an extracted tooth with multiple pinpoint entrance points in the coronal third of the root.

Figures 14 and 15 – Islands of bone-like calcified tissue (asterisk) may form surrounded by highly vascularized fibrous resorptive tissue. A trabecular bone like pattern may be noted radiographically within the ECIR defect.

Treatment

When considering whether or not a tooth with ECIR is a good candidate for treatment, our initial concern should be the location size of the defect. For example a Class II facial ECIR on a lower anterior is much more treatable than a similar sized interproximal defect. As I mentioned in part one of the blog, CBCT technology is incredibly useful when assessing resorption defects and I always have a patient scanned prior to any decision making process. ECIR can certainly be diagnosed with traditional radiographs however a 3 dimensional view is required for proper treatment planning. Performing all treatment with high magnification using a surgical microscope is also greatly advantageous.

The three main goals of treatment are as follows…

1- Perform endodontic therapy if necessary. Endodontic treatment may not be required if the ECIR is detected early (class I or class II) and the pulp is vital and testing within normal limits. However, most lesions are Class III or Class IV at the time of detection and although they may not communicate directly with the pulp they come very close so that any attempt at debridement will oftentimes result in a pulp exposure or irreversible pulpitis, making RCT necessary.

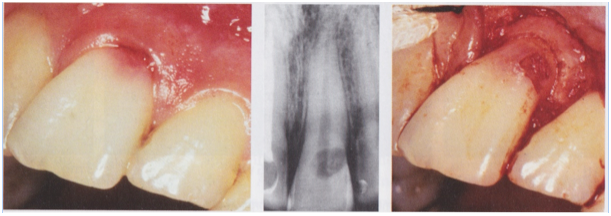

2- Attempt to remove the lesion in its entirety. The ultimate goal of treatment with ECIR lesions is to remove or inactivate all resorptive tissue. If this is not achieved, any clastic cells left behind will continue to do what they do best, destroy dentin. The compromised dentin and resorptive tissue is first debrided mechanically with a bur. Cases with small external pinpoint perforations can be accessed internally. Larger more cavernous perforations may require raising a flap for external surgical access (Figure 16) . A cotton pellet soaked in 90% Trichloracetic acid (TCA) is placed in the defect for at least one minute for the purpose of “burning out” any tissue and clastic cells that were not removed mechanically (Figure 17). The TCA causes any soft tissue contacted to undergo coagulation necrosis.

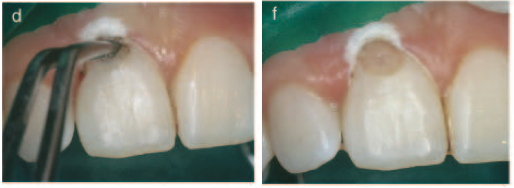

Figure 16- A sulcular incision is made and a flap raised to expose a Class III ECIR lesion on the facial of #8.

Figure 17- A cotton pellet soaked in 90% Trichloracetic acid is placed into the defect for one minute following mechanical debridement in an attempt to destroy all resorptive cells.

3- Restore the defect. A glass ionomer cement (Geristore) is the most commonly used restorative material for restoring ECIR defects (Figure 18). It is well tolerated by the periodontium when placed subgingivally and its dual cure action provides an immediate seal, unlike MTA, which has a risk of washing out due to a longer setting time. Geristore is also more esthetically acceptable and can easily be veneered with composite when necessary. The TCA has a strong demineralization effect on dentin and results in a surface that does not bond well. After using TCA, it is advised to remove a superficial layer of dentin with a slow round bur prior to etching, bonding, and restoring.

Figure 18 – The ECIR defect is resored with Geristore and the tissue reflected back into place and sutured. The image on the right shows a 6 month recall with healthy periodontium.

Prognosis

Prognosis of teeth with ECIR lesions is, not surprisingly, correlated with the size and location of the initial defect. I mentioned this previously but it is well worth repeating…the entire lesion and all clastic cells must be removed in order to stop the resorptive process. Removing the lesion may be possible however the restorability of the remaining tooth structure must always be considered. Heithersay (2004) reported that out of 100 teeth treated, a 100% success (defined by the absence of periapical pathology or the re-emergence of resorption) was achieved with Class I and II ECIR lesions (22 teeth with a mean follow up period of 4.5 and 8 years respectively). A 78% success rate was achieved with teeth containing Class III defects (63 teeth with a mean follow up period of 8 years). Predictably, Class IV lesions (16 teeth) had the poorest success rate with 12.5% (mean follow up period was unreported).

It is also important to realize that the resorption rates of ECIR lesions vary greatly. I’ve seen lesions show minimal change over a 10 year period while others progress from the invisible to a Class IV in a number of months. Consequently, it is advised to treat ECIR lesions immediately after detection if possible. An exception would be a large untreatable asymptomatic Class IV lesion. A patient in this scenario would need to understand that the tooth will be eventually lost, however they may be able to retain the tooth for a number of years if the rate of resorption was slow. Extraction would be advised upon the emergence of symptoms.

Recent Cases

The following are cases I have recently completed at our office.

Case #1

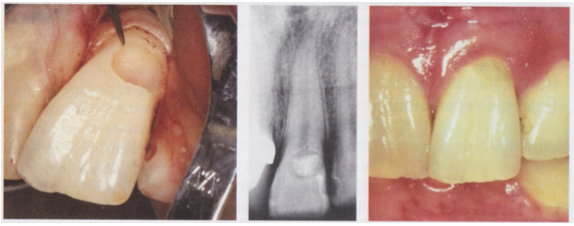

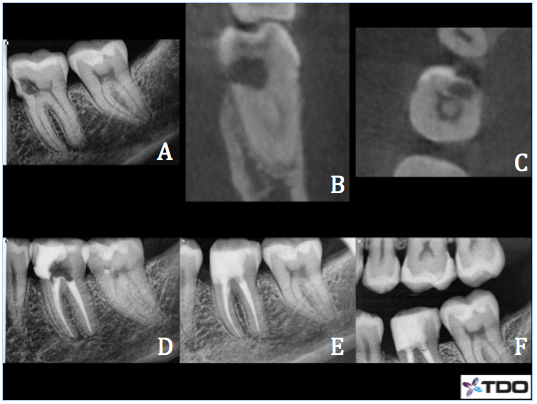

Case 1-#27 Class III ECIR with external surgical repair

63 y/o female presented to our office for the evaluation of tooth #27. B root surface filling placed many years ago and current dentist suspected resorption after raising an exploratory flap. Patient was asymptomatic. Radiographic and CBCT exams reveal a B surface composite filling surrounded by what appears to be an ECIR Class III. CBCT reveals the resorption extends into the coronal 1/3rd of the root and to within close proximity of the pulp (B). No evidence of periapical bone loss and apical tissues appear WNL. The tooth responded WNL to cold testing and pulp was vital. B surface access was made because the tooth was partially rotated, making the lingual surface unavailable for traditional access. Pulpectomy was completed and the canal was medicated with Ca(OH)2. Patient returned 4 weeks later for the completion of RCT (C,D). The coronal 1/2 of the canal was filled with with Geristore (blue highlight) so that excavation of the external resorption resulted in contact with glass ionomer material rather than gutta percha. B access was restored with flowable composite (purple highlight). A sulcular flap was raised and the existing composite and the ECIR lesion was debrided. The prep was soaked with 90% trichloracetic acid and then restored with Geristore (E). The flap was re-approximated and sutured in place with 5-0 interrupted vicryl sutures. Patient remained asymptomatic at her 6 months recall(F). Soft tissues appeared WNL. No gingival swelling. Perio probings were 1-2mm and WNL. Apical tissues appeared normal.

Case #2

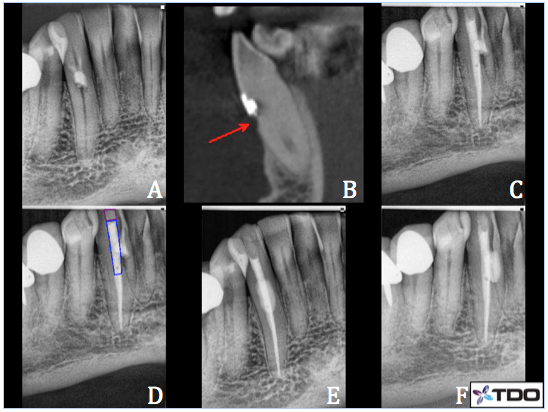

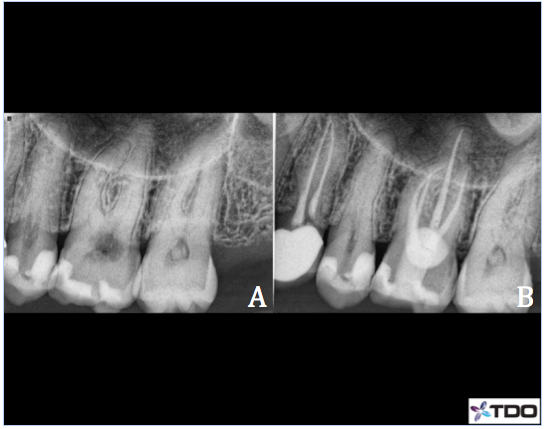

Case 2– #8 Class III ECIR with internal repair

62 y/o female presented complaining of biting tenderness and cold sensitivity. CBCT sagittal (B), coronal (C), and axial (D) slices showed a well defined cavernous ECIR lesion with a large lingual perforation. The lesion also communicated with the pulp. Apical PDL space is thickened. Prognosis is guarded however patient was very motivated to save the tooth at all costs. Recommend RCT followed by a surgical repair of the ECIR lesion. Pulpectomy was completed and Ca(OH)2 packed into the pulp system. The patient returned a few weeks later and RCT was completed. I was able to debride the ECIR defect very well via the lingual access and did not find it necessary to raise a surgical flap. I placed a cotton pellet with 90% trichloracetic acid over the resorbed area after prepping to burn out any remaining clastic cells. Geristore was used to fill in the defect and lingual access. Recall not yet available.

Case #3

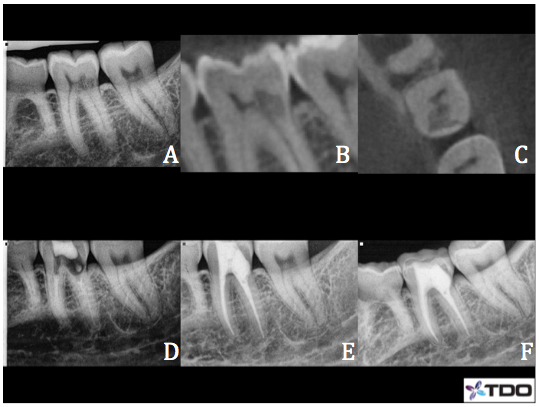

Case 3– #19 Class II ECIR with LuxaCore buildup

33 y/o female presented complaining of an intermittent dull ache and hot/cold sensitivity. Radiographic and CBCT exams revealed Class II ECIR overlying the M pulp horn and extending to the ML osseous crest (A, B, C). Clinical exam revealed secondary caries had infiltrated the lesion, resulting in an irreversible pulpitis. Endodontic treatment was completed on the first visit and the tooth was temporized with cotton and cavit (D). The patient returned a week later and the ECIR defect was prepped out. I soaked the area with 90% trichloracetic acid to ensure the removal of all resorptive tissue. An MOBL LuxaCore (dual cure composite) buildup was placed (E, F) and the patient was referred back to her general dentist for the crown. Recall not yet available.

Case #4

Case 4– #14 ECIR Class III with external surgical repair

48 y/o female presented complaining of a food trap on the palatal surface of #14. She was not experiencing any discomfort. Clinical exam revealed a circular ECIR lesion of about 5mm in diameter on the L surface of #14, extending 1mm subgingivally. The tooth tested WNL to cold was the pulp was vital. Radiographic exam revealed the lesion was superimposed over the pulp chamber and mostly within the cervical 1/3rd of the clinical crown. Apical tissues were WNL and there was no evidence of periapical pathology. Because the lesion is mostly supragingival secondary decay was noted and excavation resulted in a pulpal exposure.

Endodontic treatment was completed. The coronal 3mm of the P canal was filled with Geristore in preparation for the ECIR repair. Palatal tissue was reflected to gain full access to the defect. All decay and resorptive tissue was removed mechanically and I soaked the prep with 90% TCA. Geristore was placed as a restoration and the flap was re-approximated and sutured into place. The patient was referred to her general dentist for the crown. Recall not yet available.

Case #5

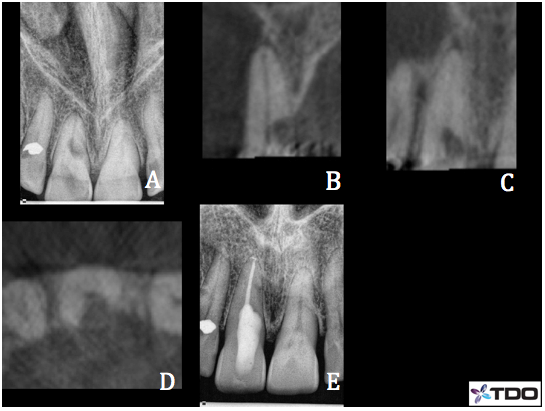

Case 5– #19 Class II ECIR with internal repair

44 y/o female presented for the evaluation of #19 due to a Class II ECIR lesion that was discovered on a routine bitewing. Patient was asymptomatic. The tooth was vital and testing WNL to cold. Apical tissues appeared WNL. CBCT sagittal slice (B) showed the ECIR lesion is limited to the coronal tooth structure and appears to communicate with the pulp chamber. Axial slice (C) showed small, pinpoint root surface perforations on the DL and DB line angles.The pulp tissue was extirpated and pulpectomy was completed. NaOCl/EDTA/CHX irrigation. Ca(OH)2 was packed to the apices. Each canal was covered with a small cotton pellet and Opaldam. I then excavated the ECIR lesion and the area was soaked with 90% trichloracetic acid. I then patched the perforations with Geristore (D) and temporized with cotton and cavit. Patient returned after a couple of weeks and remained asymptomatic. Endodontic treatment was completed and I restored the defect and completed the buildup with Geristore (E). The patient was referred back to her general dentist for the crown. Patient remained asymptomatic at her 6 month recall (F) and crown had been placed.

In conclusion, ECIR can be a very difficult condition to treat and patients’ expectations need to be realistically managed via open and honest communication. Fortunately as the ECIR becomes more understood and early diagnosis more frequent, prognosis has become more favorable, especially when CBCT imaging is utilized as well as modern techniques using a surgical operating microscope. Although very technique sensitive and challenging, I find treating ECIR cases to be incredibly rewarding, and there is nothing more satisfying than saving a patient’s tooth!

Hope you enjoyed this week’s blog and thank you for reading!

References

Cohen, S., Hargreaves, K.M. and Berman, H.M. (Eds.). (2011) Cohen’s Pathways of the Pulp (10th edition). MOSBY Elsevier.

Heithersay GS. Invasive cervical resorption. Endod Topics 2004;7:73–92.3.

Patel S, Kanagasingam S, Pitt Ford T. External cervical resorption: a review. J Endod 2010;35:616–25.

Schwartz et al. Management of invasive Cervical Resorption. Observations from Three Private Practices and a Report of Three Cases. J Endod 2010;36:1721-1730

Thanks for visiting Tri City and Fallbrook Micro Endodontics of San Diego, CA.